Tiny Recursive Model (TRM): A Deep Dive

Deep dive into the architecture and inner workings of the 7M parameter Tiny Recursive Model (TRM) that beats the most advanced reasoning LLMs on complex problems.

A new class of AI models is emerging. It’s called the Recursive Reasoning Model.

The architecture of the earliest recursive reasoning model, called the Hierarchical Reasoning Model (HRM), was published by Sapient Intelligence in early 2025.

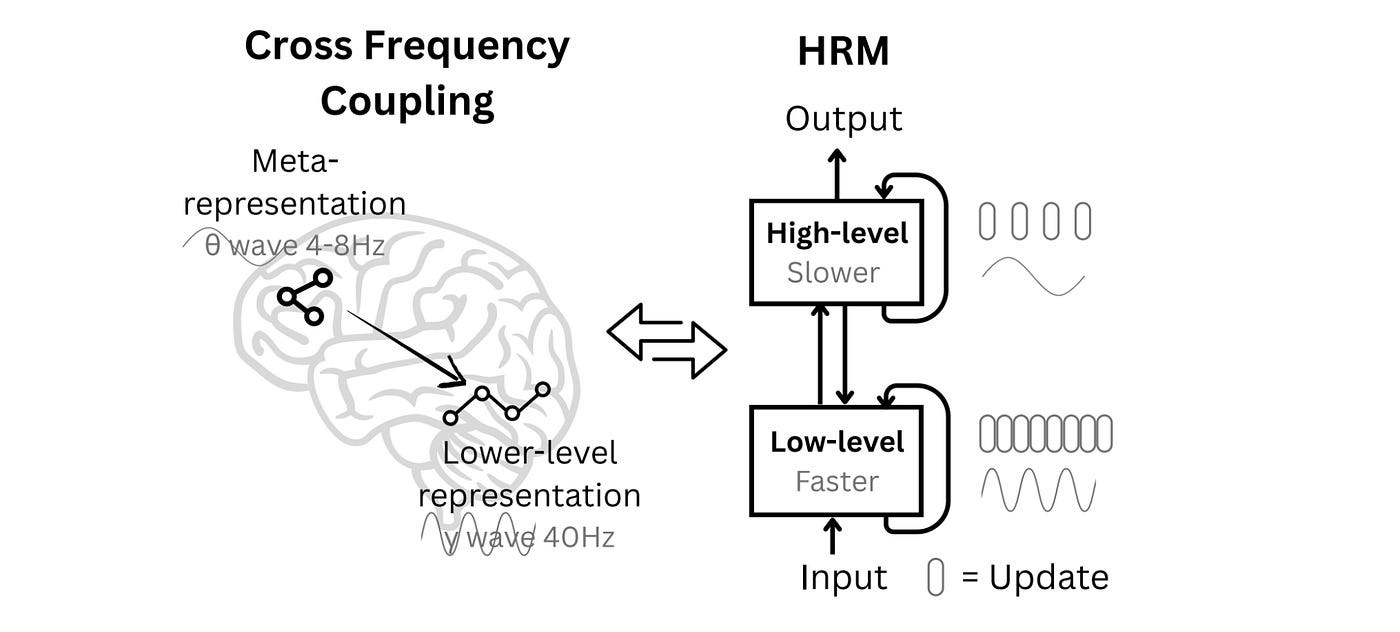

The biologically inspired HRM consists of two interdependent neural networks operating at different frequencies (one updating faster than the other).

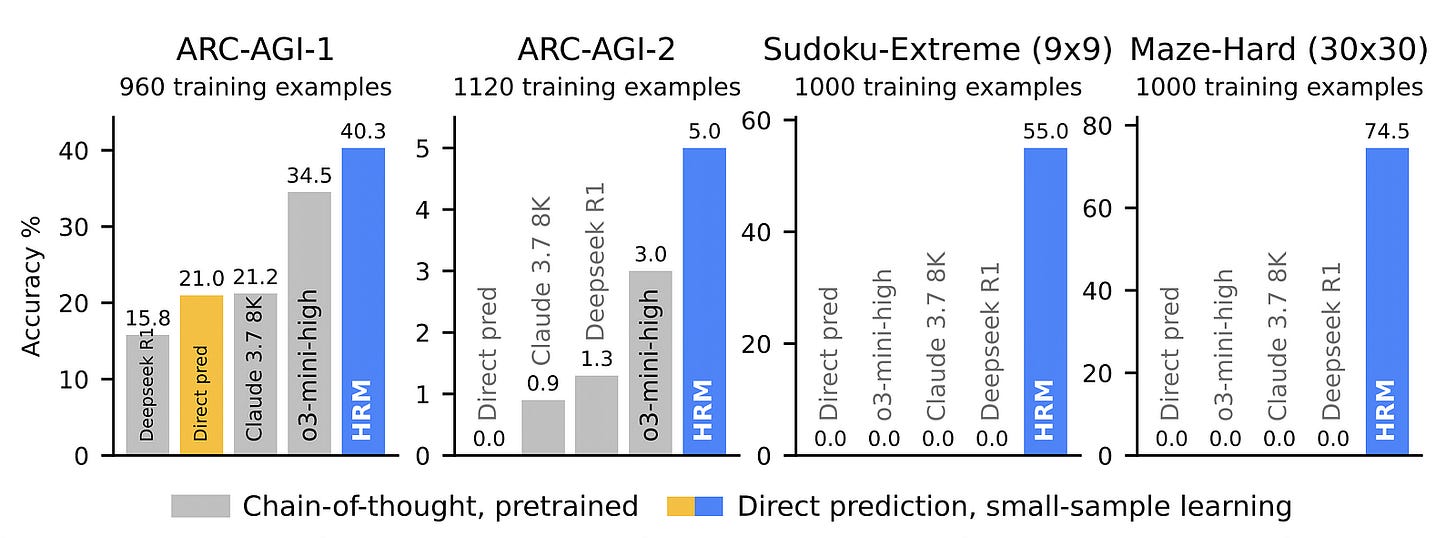

With just 27 million parameters, it outperforms powerful LLMs on complex tasks, such as solving challenging Sudoku puzzles, finding optimal paths in large mazes, and on ARC-AGI, when trained using only 1,000 examples.

While these results were impressive enough, new research published by a researcher at Samsung SAIT AI Lab has improved HRMs to reach even better performance.

Their newly proposed Tiny Recursive Model (TRM) uses a single small network with only two layers.

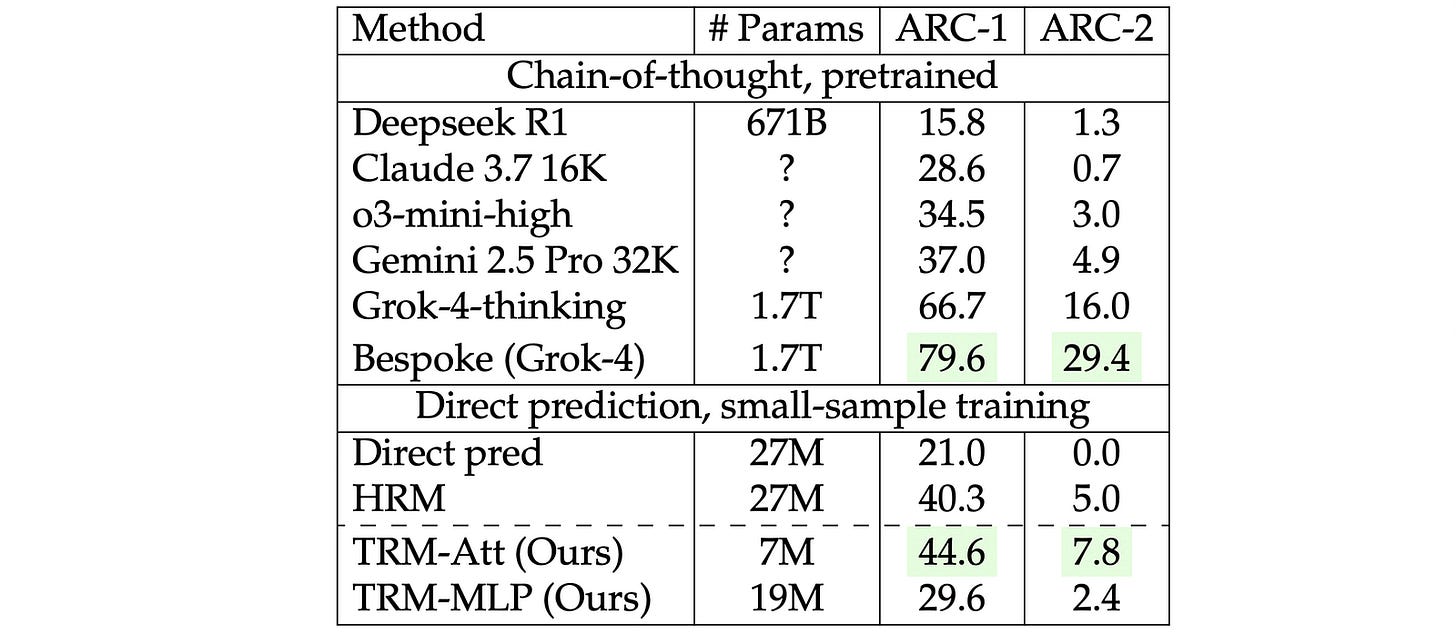

With only 7 million parameters, the TRM achieves a test accuracy of 45% on ARC-AGI-1 and 8% on ARC-AGI-2. (If you’re new to them, ARC-AGI benchmarks are specifically designed to act as a helpful signal for reaching AGI.)

This is a better result than most advanced reasoning LLMs available today (including Deepseek R1, o3-mini, and Gemini 2.5 Pro), achieved with less than 0.01% of their parameters.

Here is a story where we understand the architecture and inner workings of the Tiny Recursive Model (TRM) and explore the reasons why it beats most advanced reasoning LLMs available to us today.

Let’s begin!

Before we start, I want to introduce you to my new book called ‘LLMs In 100 Images’.

It is a collection of 100 easy-to-follow visuals that describe the most important concepts you need to master LLMs today.

Grab your copy today at a special early bird discount using this link.

But First, How Do LLMs Reason?

Reasoning in LLMs is a popular area of AI research.

To ensure that LLMs can reliably answer complex queries, they use a technique called Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. CoT imitates human reasoning by having the LLM produce step-by-step reasoning traces before giving its final answer.

Using CoT involves generating more tokens during inference (called Inference-time scaling), which in turn means using more inference compute. Generating high-quality CoT traces also means training the LLM to do so by using high-quality training datasets using expensive RL techniques.

Despite their extensive use, CoT-based LLMs still fail on benchmarks like ARC-AGI. As an example, while humans can fully solve the tasks in ARC-AGI-2, OpenAI’s o3 (high) achieves merely 6.5% accuracy on it.

A ray of hope emerged with the introduction of the Hierarchical Reasoning Model (HRM) in early 2025, which, with only 27 million parameters and using only 1000 training samples, achieved exceptional performance on complex reasoning tasks, including ARC-AGI.

To understand Tiny Recursive Models, you’ll have to understand HRMs well. Let’s learn about them in depth before proceeding further.

What Is The Hierarchical Reasoning Model (HRM)?

The HRM architecture is inspired by the human brain and consists of four components:

Input network (

f(I)), which converts a given input into embeddings, passing it to the low-level moduleA faster, low-level module (

f(L)) for detailed computations (the “Worker” module)A slower, high-level module (

f(H)) for abstract, deliberate reasoning (the “Controller” module)Output head (

f(O)), which gets the output from the high-level module and produces a final output

Both low and high-level modules follow the 4-layer Transformer architecture, with:

No bias in linear layers (following the PaLM architecture)

Rotary embeddings, and

SwiGLU activation function

Understanding A Forward Pass In An HRM

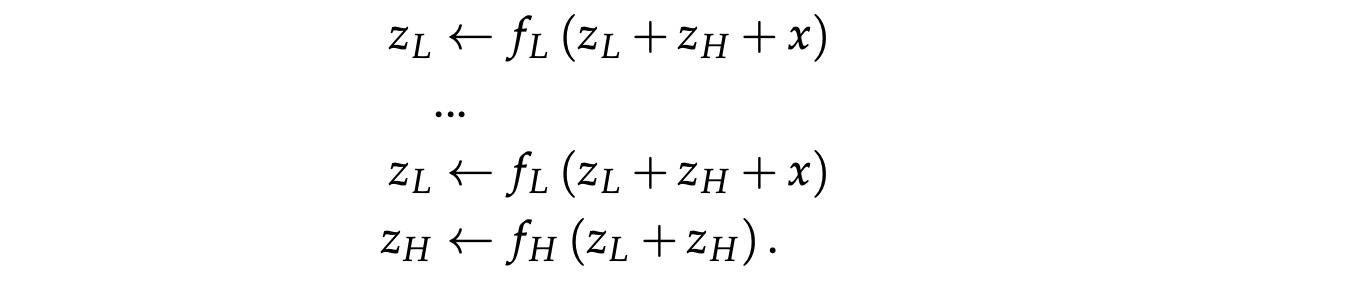

Given an input x̃, the high-level and low-level modules start with their initial latent vectors (z(H) and z(L), respectively) and recursively update them.

The low-level module updates z(L) at a higher frequency, and the high-level module updates z(H) at a lower frequency.

After recursion, the latent vector of the high-level module z(H) is used to reach the final answer ŷ using the output head.

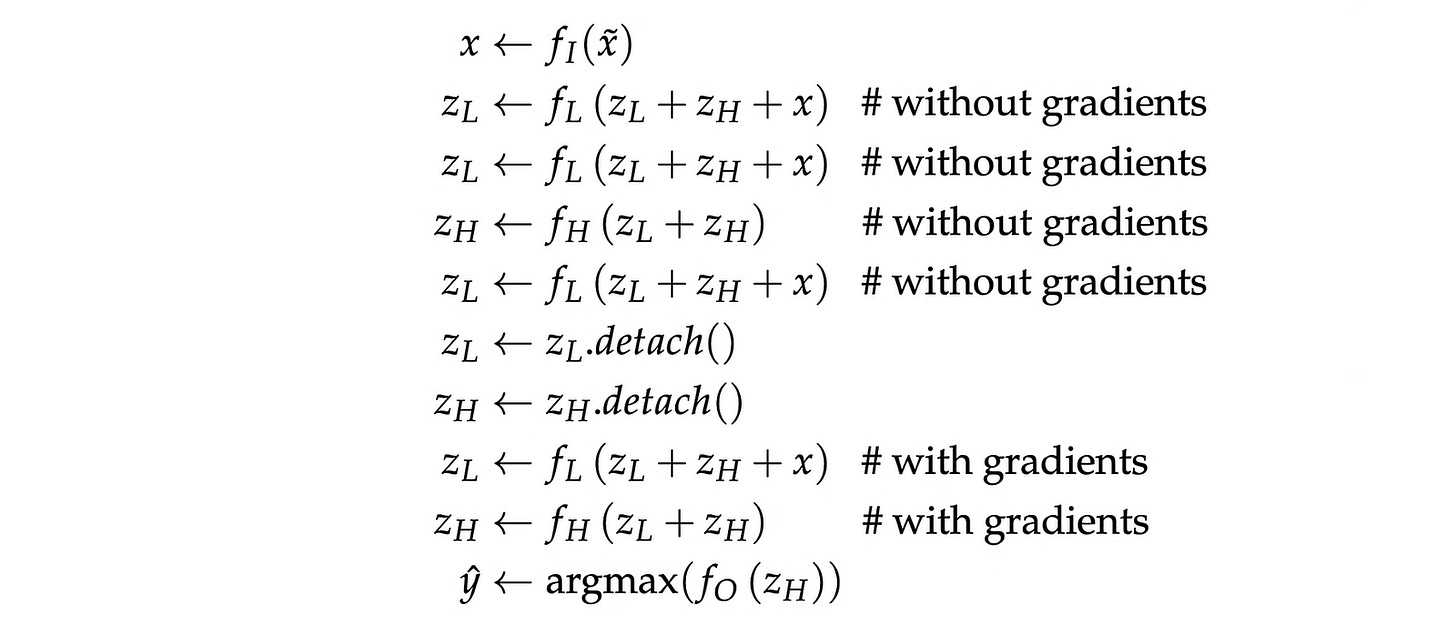

Mathematically, a forward pass of HRM looks as follows:

Let’s understand this step by step.

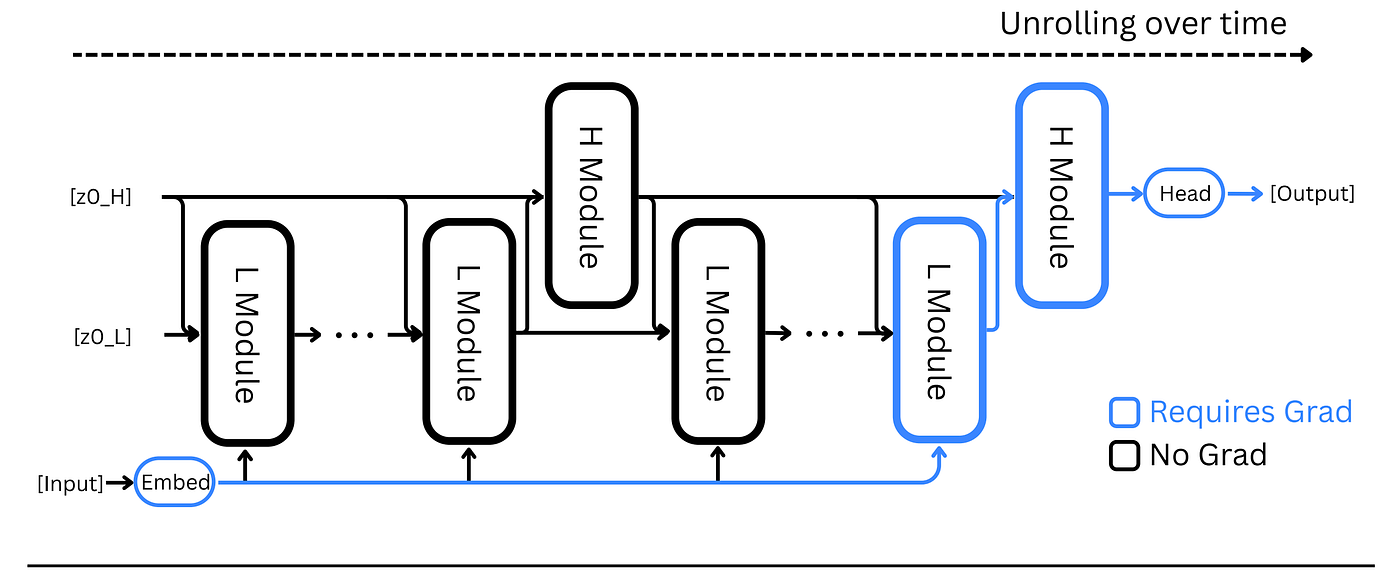

Given an input x̃, it is passed through the input network f(I) to create an embedding x. (Step 1)

This embedding, along with the latent vector from both modules, is passed through the low-level module. (Step 2)

After two low-level updates, the high-level module is updated just once. Following this, the low-level module is updated once again. (Steps 2–5)

It is assumed that these steps help move the latent vectors closer to a fixed point or a stable internal reasoning state.

No gradient flows backward in these steps during training, and both latent states z(L) and z(H) are detached from the computation graph. (Steps 6–7)

Following this, both modules are updated one more time, but this time with gradient tracking turned on. This is the single gradient-tracked step where all learning actually happens. (Steps 8–9)

Finally, the high-level module’s latent vector z(H) is passed through the output head f(O) to produce logits that are selected using the argmax function to reach the final prediction ŷ. (Step 10)

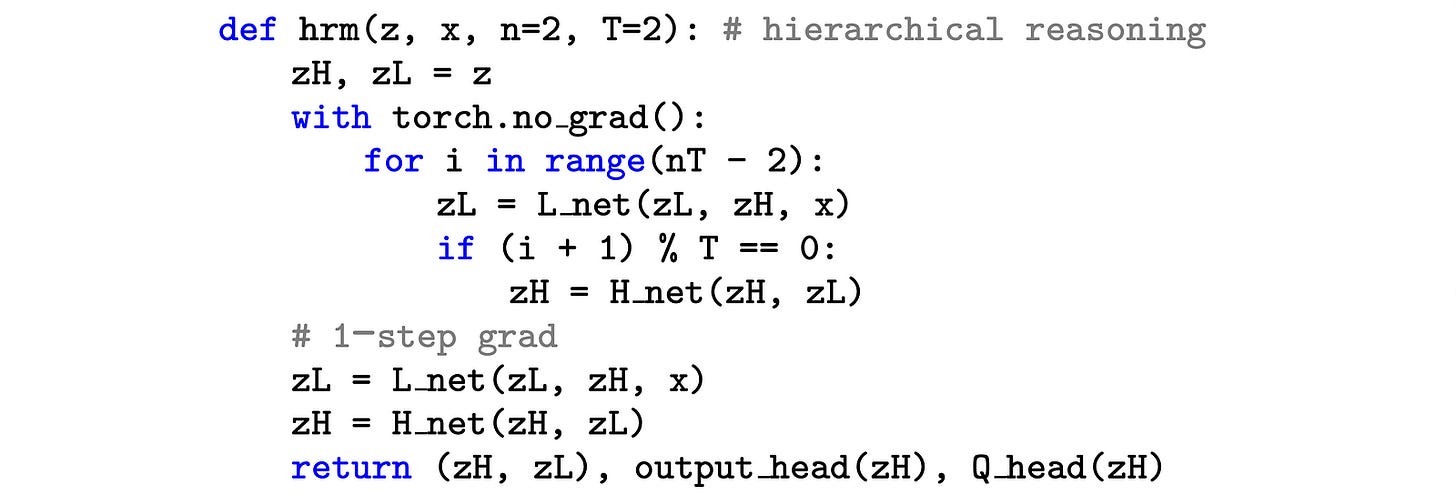

The pseudo-code for these steps is shown below.

One-step Gradient Approximation

Did you notice that the gradients were tracked in just the last two steps?

This is because it is assumed that the latent state/ vectors of both modules reach a fixed stable point while recursing through these modules.

From this point, the Implicit Function Theorem with the one-step gradient approximation (described in detail here) is used to approximate the gradient by backpropagating only the last steps. This step greatly saves on memory requirements.

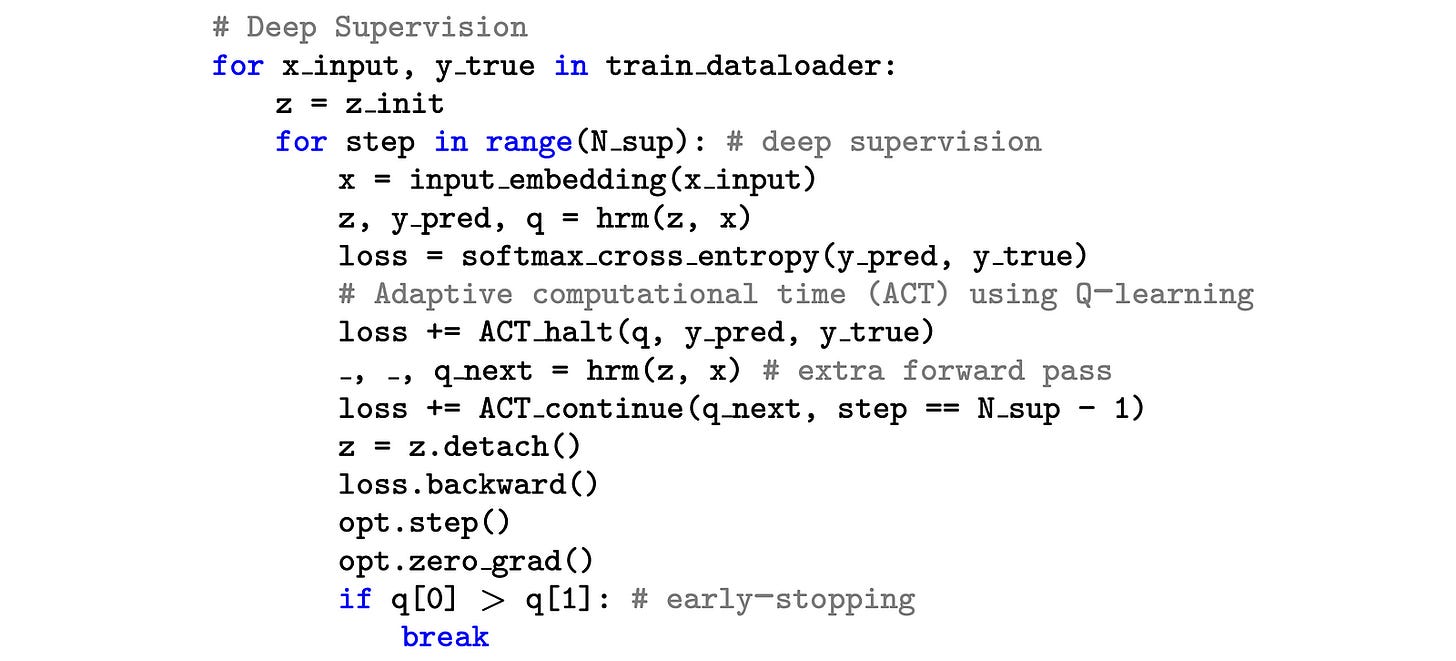

Deep Supervision & Adaptive Computational Time (ACT)

To simulate a very deep neural network, a process called Deep Supervision is used during training.

Given a training data sample denoted by (x, y), where x is the input and y is the label, respectively, multiple supervision steps are run, with each step producing its own prediction and loss.

After each recursion cycle, the latent states of both modules are detached and used as the starting point for the next supervision step.

At most, 16 such supervision steps are used.

This allows the model to be trained not only on the final output but also on multiple intermediate stages of its reasoning process, while simultaneously saving memory.

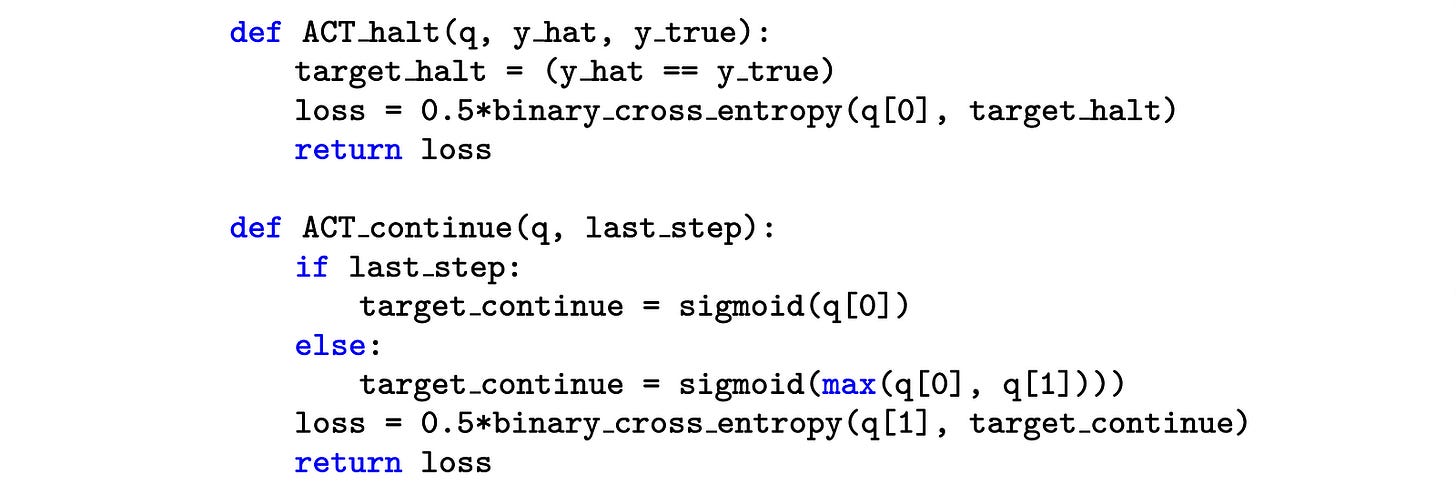

During training, a method called Adaptive Computational Time (ACT) is used, which determines the number of supervision steps to apply for each training example.

It uses a Q-learning objective to predict whether to halt or continue based on intermediate outputs obtained by passing z(H) through an additional head and running an additional forward pass.

If this method predicts that it has already learned enough from a training data sample, it stops early, which reduces training time while maintaining performance.

Both Deep supervision and One-step gradient approximation help an HRM to learn so well without the need for very deep neural networks.

Could HRMs Be Improved Further?

The author introducing TRM finds three areas of improvement in the HRM architecture. These are described as follows.

Firstly, although HRM relies on two networks operating at different hierarchies based on biological arguments, it is unclear if the use of this exact number of networks and features (two latent vectors) is justified.

Next, the HRM architecture assumes that the high-level and low-level recursive networks converge to a fixed point after just four steps. The gradients then computed at this fixed point can approximate full backpropagation.

However, it is seen that neither of these networks converges fully within these few steps. Therefore, applying the Implicit Function Theorem (IFT) for one-step gradient approximation after these steps may not be the best option.

Finally, HRM uses Adaptive Computational Time (ACT) to prevent the model from spending excessive time learning from a single training data sample.

For this, ACT uses a Q-learning objective with a halting loss and a ‘continue’ loss. The ‘continue’ loss requires an extra forward pass through the HRM. This means that while ACT makes training per sample more efficient, it requires two forward passes per optimization step, which makes its overall use inefficient.

These three targets are improved on in the Tiny Recursive Model (TRM).

Moving Towards The Tiny Recursive Model (TRM)

Let’s discuss the changes in the HRM architecture that led to the TRM.

1. Adapting A Single Neural Network

Unlike HRM’s low and high-level modules, which operate at different frequencies, TRM uses a single network that performs both tasks.

This is based on the fact that the different roles of the two networks in HRM are actually defined by the inputs they receive.

When an input contains x (refer back to Step 1 of the forward pass of HRM), the network acts like the low-level module, doing reasoning using the input and the current solution. Otherwise, it acts like the high-level module updating the solution using only the latent state.

2. Reducing The Number Of Layers

Unlike HRM’s 4-layer Transformer modules, the TRM uses just two layers in them. Alongside reducing the layers, the number of recursive steps is increased proportionally to keep the effective depth and total compute the same.

The reason for this change is that a rising number of layers leads to poor performance as the model tends to overfit on the small training dataset.

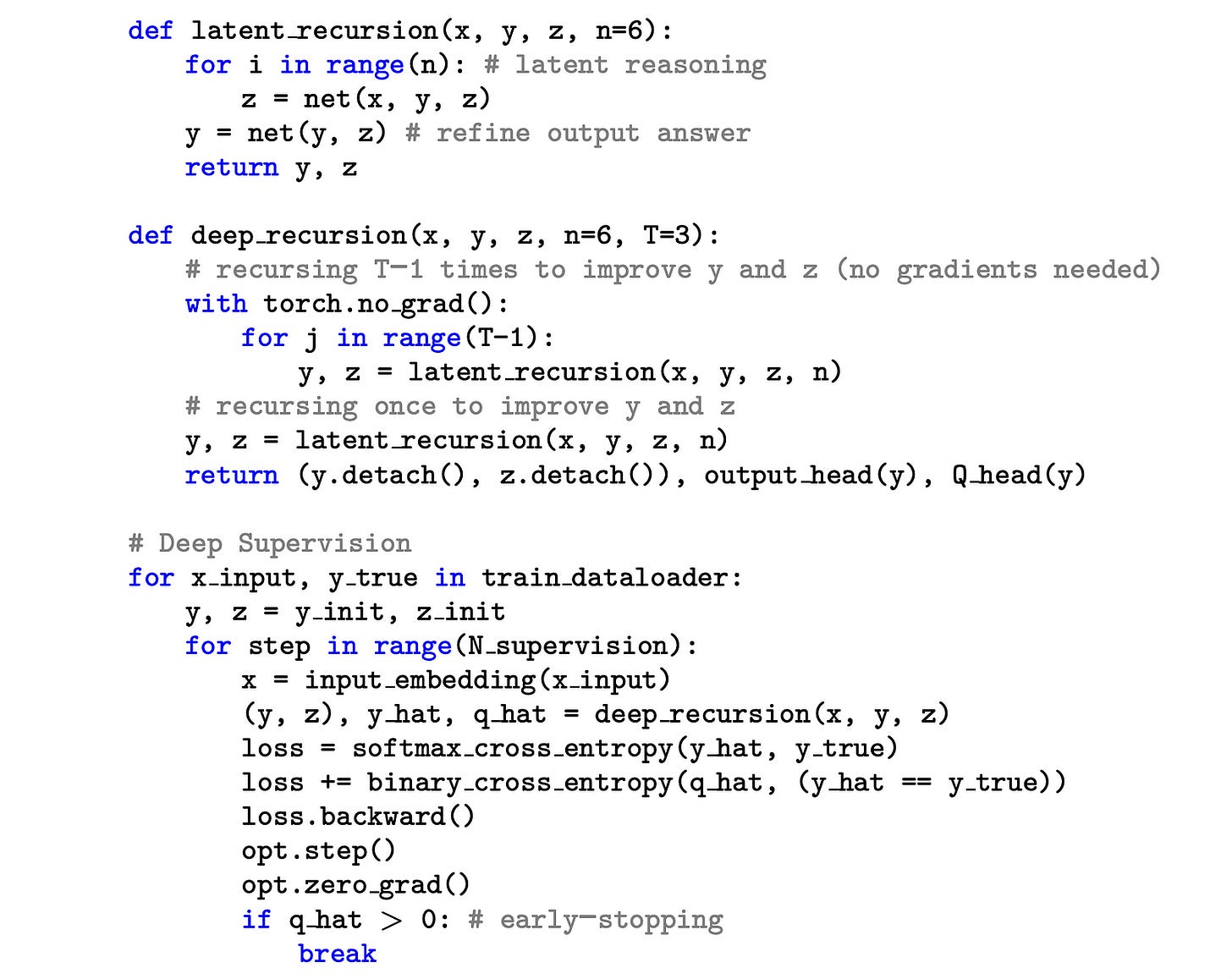

3. Discarding The Use Of One-step Gradient Approximation

TRM removes the need for one-step gradient approximation. Instead, several recursion cycles are run without gradients first, followed by one full recursion with gradients.

4. Removing The Extra Forward Pass in ACT

Instead of using two losses (halting and ‘continue’ loss in HRM), the TRM gets rid of the ‘continue’ loss and uses just the halting loss.

The halting loss is a binary cross-entropy loss that trains the model to predict when to halt or stop processing a training data sample at each supervision step.

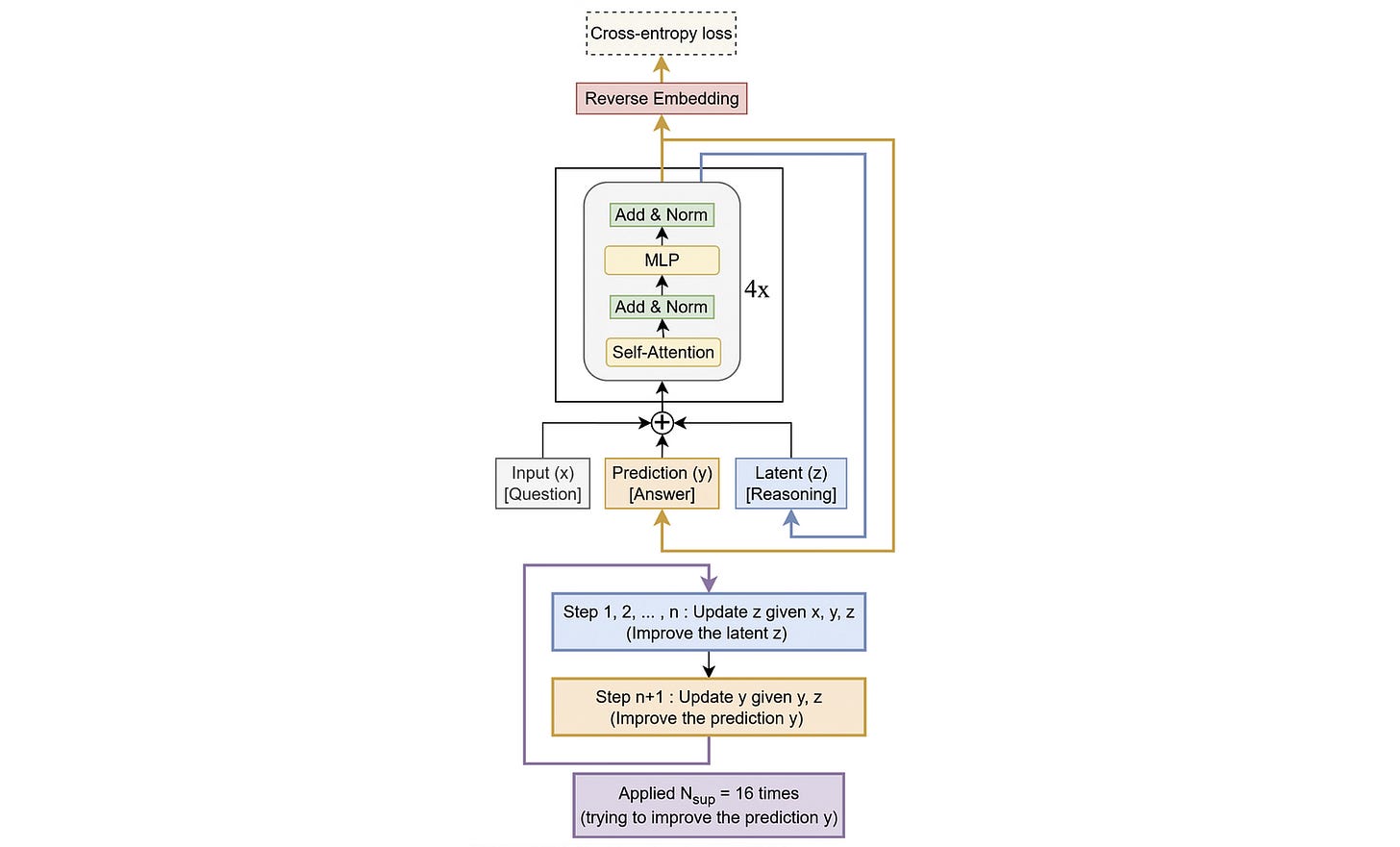

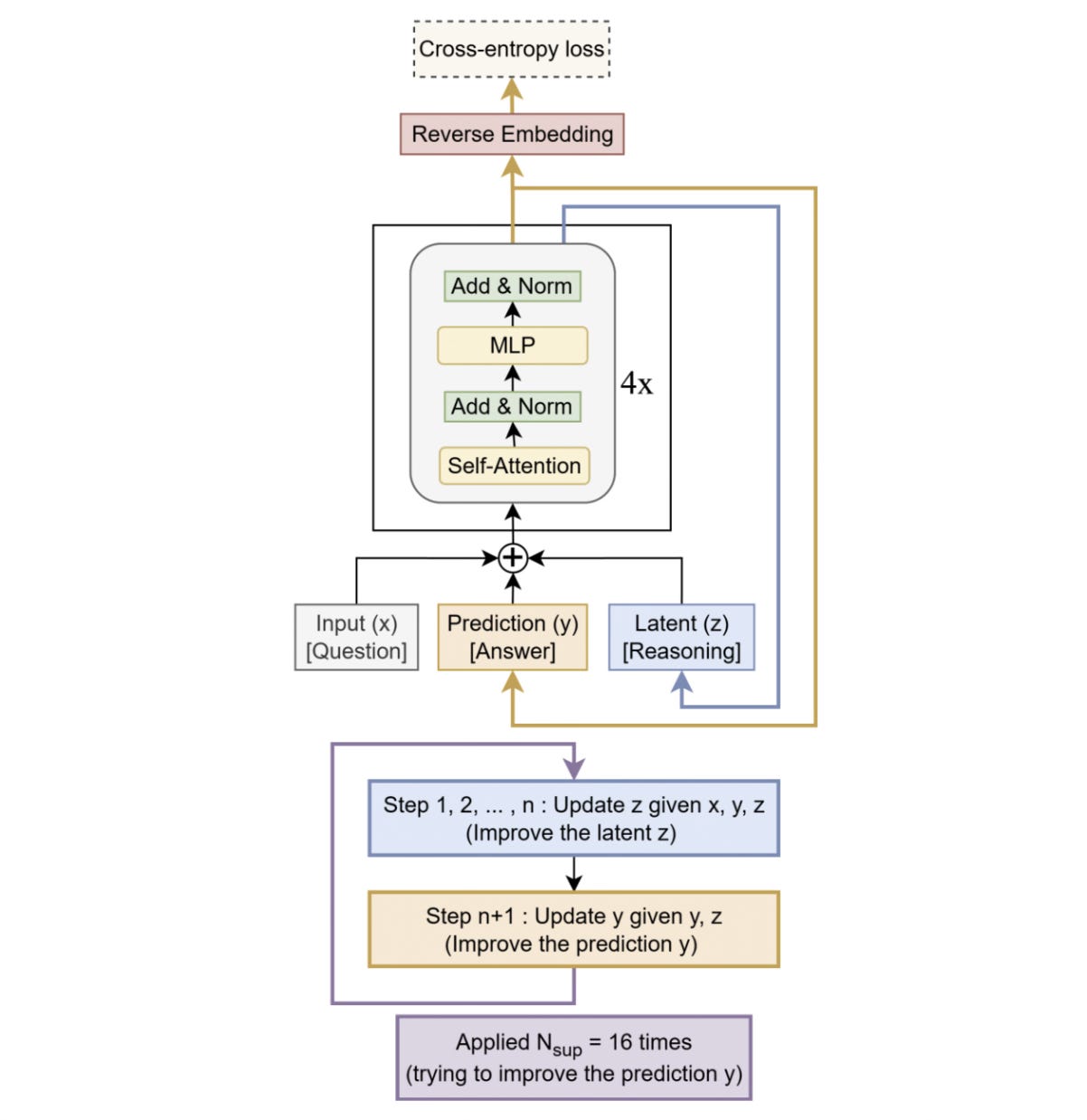

How Does The TRM Work?

The core idea behind the TRM, similar to the HRM, is to start with an initial guess for the answer to a problem and iteratively improve it through recursion.

It starts with three elements as follows:

x: The input embedding (similar toxin an HRM)y: The current predicted answer (similar toz(H)in an HRM)z: A latent representation that the model uses to reason when arriving at its prediction (similar toz(L)in an HRM)

During each recursive step, the latent reasoning representation z is updated n times based on the input x, current prediction y, and the previous latent state z. After n latent updates, the predicted answer y is updated once using the newly updated latent state z.

This full recursion process is then repeated T times in total. The first T−1 recursions are performed without backpropagation, while the final recursion is run with backpropagation.

After T recursions, deep supervision is applied. During this, the model computes a prediction from the current value of y by passing it through the output head. This prediction is then compared against the ground-truth target using a loss function. Finally, the loss is used to update the model’s weights.

This deep supervision can go on for N_supervision cycles during training, with each cycle containing T x (n + 1) steps.

Alongside this, a halting mechanism (q_hat) predicts whether the current answer is correct. If so, the model stops recursion early (before completing all N_supervision cycles) during training to save on compute.

However, at test time, the total N_supervision cycles are always used to maximize performance.

The architecture of the Tiny Recursive Model (TRM) is shown below.

Let’s next look into the impressive results that the TRM leads to.

A Look Into TRM’s Spectacular Results

For experiments, a TRM is trained on the following datasets:

Sudoku-Extreme: A dataset of highly challenging 9 × 9 Sudoku puzzles

Maze-Hard: A dataset of complex 30 × 30 mazes that tests optimal path finding capability

ARC-AGI-1 and ARC-AGI-2: Dataset of questions that test general intelligence using puzzles that require inductive reasoning.

The AdamW optimizer is used with softmax cross-entropy loss as the primary training loss and binary cross-entropy as the halting loss.

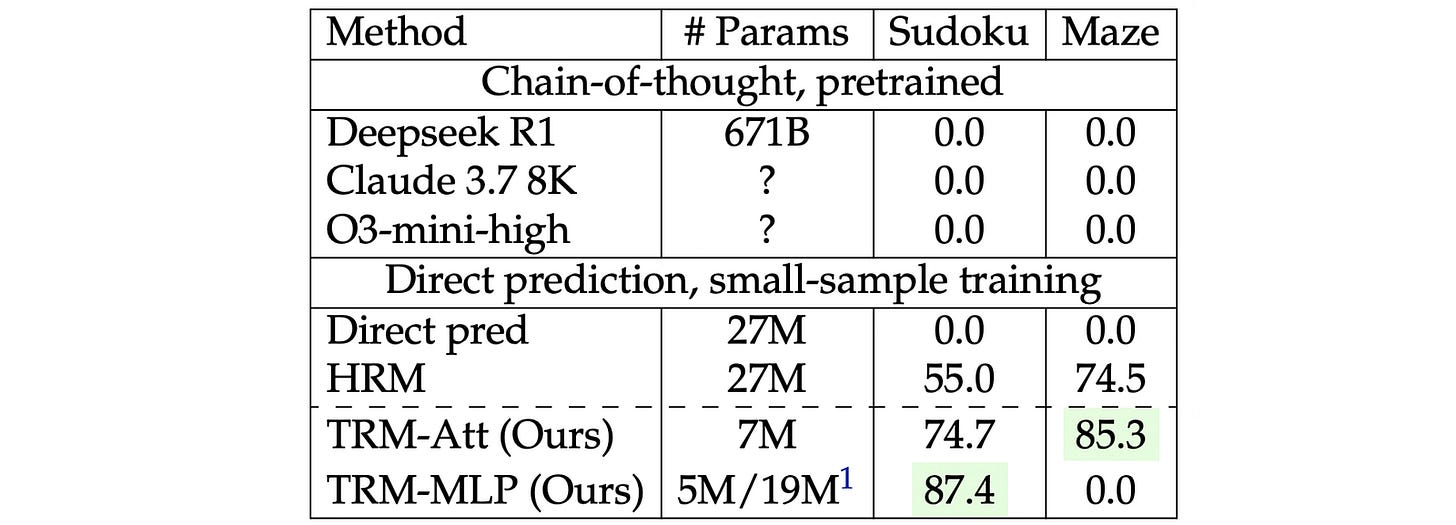

TRM obtains a test accuracy of 85.3% on Maze-Hard, 44.6% on ARC-AGI-1, and 7.8% on ARC-AGI-2 with just 7M parameters.

This is significantly higher than the HRM, which achieves 74.5%, 40.3%, and 5.0% test accuracy on these datasets, respectively, while using four times the number of parameters (27M).

Training on just 1000 samples from the Sudoku-Extreme dataset, the TRM achieves a test accuracy of 87.4%. This is again higher than the HRM, which gets a 55% test accuracy.

Why Is It Still Unfair To Compare LLMs With TRMs

It’s surprising how TRMs, while being so small, can get such high accuracies on these tough benchmarks, while reasoning LLMs with billions of parameters fail badly on them.

Recursive hierarchical reasoning and Deep supervision seem to be the secret sauce behind these results.

Although impressive, it is worth noting that TRMs are trained using supervised learning to predict a single specific answer. They aren’t generative models and do not have an impressive performance across a wide variety of tasks like reasoning LLMs do.

TRM’s performance is also based on architectural choices. For example, replacing self-attention with MLP layers results in an improvement in its performance on Sudoku-Extreme. This is not the case with LLMs when they are applied to solve different problems.

Also, unlike LLMs, where scaling up parameters usually improves performance, TRMs actually perform worse with more parameters or layers, which could be a result of overfitting on small datasets, such as Sudoku-Extreme.

Because these models behave differently from LLMs, new scaling laws are needed to find their best-performing configurations.

It is for these reasons that it is unfair to compare them to reasoning LLMs. However, all in all, TRMs are an impressive step towards improving reasoning for solving complex tasks.

It would be interesting to see how they are applied alongside LLMs to reach superintelligence.

Further Reading

Research paper titled ‘Less is More: Recursive Reasoning with Tiny Networks’ published in ArXiv

Github repository containing the code for the TRM research paper

Research paper titled ‘Hierarchical Reasoning Model’ published in ArXiv